Speech Production

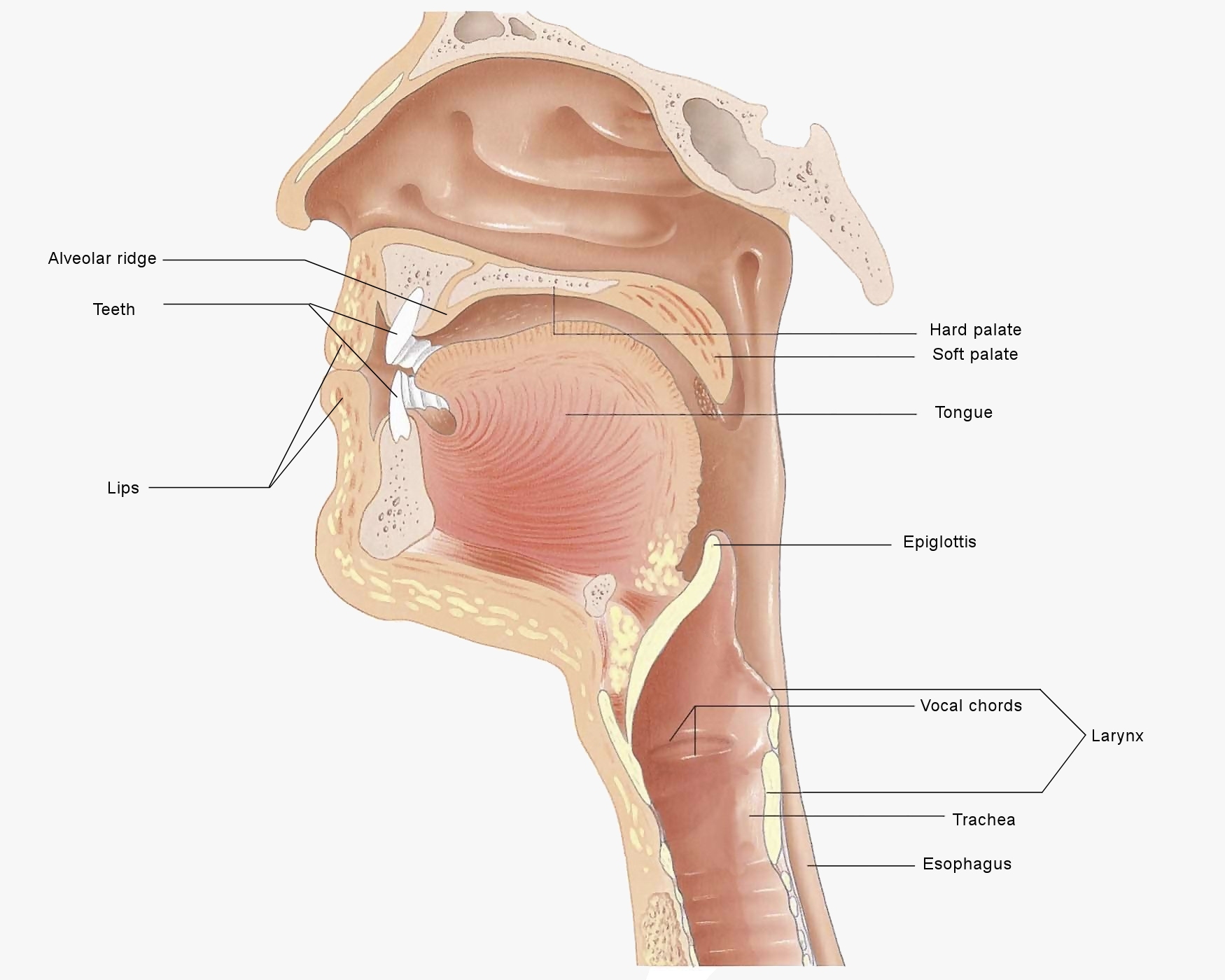

Humans are capable of producing a great variety of distinct speech sounds. The approximately 5,000 languages that humans speak use over 850 different sounds. The capability of humans to produce such a variety of vocal sounds, far more than any other animal, is a result of the unique structure of the human vocal tract, which includes the lungs, trachea, larynx, nasal cavity, and structures in the mouth.

Human Vocal Tract

The structures that produce human speech can interact in a variety of ways to produce a large range of sounds. This video shows some of the interactions of the parts of the human vocal tract during the production of speech.

Describing Sounds

The sounds that are combined into speech can be described by the manner in which they are produced, that is, by how the various structures in the vocal tract perform to produce the sound.

The initial process in speech production is the forcing of air out from the lungs. In a few human languages, some sounds are produced by inhaling air into the lungs, and some sounds – clicks, for example – are produced without involving the lungs. In American English, however, all speech sounds involve exhaling from the lungs.

When we are not speaking, we breathe about 15 times per minute. Breathing occurs in two phases, inhalation (drawing the air in) and exhalation (sending the air out), that are approximately equal in duration. While speaking, however, we inhale quickly, in less than a second, then extend the exhalation to several seconds.

At the start of a speech sound, the muscles of the diaphragm push air out of the lungs, through the trachea, and up to the larynx. At the larynx, the air must pass between two small flaps of muscle, which are called the vocal chords.

The air passing between these flaps can cause them to vibrate. The frequency at which they vibrate affects the pitch of the vocal sound that will be produced, and that frequency is, in turn, affected by the size and tension of the vocal chords. Smaller vocal chords vibrate more quickly than larger ones, and thus, produce higher pitched sounds. The size depends on the age and sex of the person. Young humans have smaller vocal chords than adults, and females tend to have smaller vocal chords than males, which is why children and women tend to have higher-pitched voices than men. The tension of the vocal chords is controlled by the muscles that compose them. When the muscles are contracted, they become stiffer, and they vibrate more rapidly and produce higher-pitched sounds. When the muscles are relaxed, they become more flexible, and they vibrate more slowly and produce lower-pitched sounds. By controlling the tension of the vocal chords, humans can vary the pitch of their voices.

The vibrations of the vocal chords are, in a sense, the raw material of speech. The truly remarkable variety in human speech is produced by structures above the larynx and vocal chords. These structures include the mouth and nasal cavity, which are together called the vocal tract. By moving various muscles in the vocal tract, we restrict and direct the exhaled air, adding tremendous variety to the vibrations that started with the vocal chords. These movements in the vocal tract are called articulation. Speech sounds are most often described in terms of articulation, that is, in terms of how the structures in the vocal tract are configured to produce the sounds.

Human Vocal Sounds

The sounds of speech can be classified into two major categories, vowels and consonants. A vowel is a sound that is produced with vocal cords vibrating and an open vocal tract, so that air pressure does not build up. A consonant is a sound that is produced with or without the vocal cords vibrating, but with a complete or partial obstruction of the vocal tract, so that air pressure does build up. Generally, speech is a sequence of sounds called syllables. Each syllable is composed of a vowel sound that may be preceded or followed or both by a consonant sound.

Vowels

Humans produce a variety of sounds that are classified as vowels. These vowels are distinguished by how the sounds are produced. The position of the tongue in the mouth and the shape of the lips are significant. Some vowel sounds are produced with the tongue held high near the roof of the mouth (such as the e sound in feet), others with the tongue held low in the mouth (such as the a in father).

Some vowel sounds are formed with the tongue held back in the mouth (such as the au in caught), others with the tongue held forward (such as the ai in bait).

The position of the lips also affects the sound of a vowel. Some vowels are sounded with the lips held in a rounded form (the oo in boot), others with the lips unrounded (the au in baught).

Vowel sounds, then, can be described by how the structures of the vocal tract form them. There are various combinations of these structures, and American English uses several of them. For example, there is a high, back, rounded vowel sound, in which the tongue is high and toward the front in the mouth, and the lips are rounded: the u in true. There is a low, back, rounded vowel sound, in which the tongue is low and toward the back in the mouth, and the lips are rounded: the o in both. There is a high, back, unrounded vowel sound, with the tongue high and toward the back of the mouth, and the lips are unrounded: the u in put. There is a high, front, unrounded vowel sound, with the tongue high and toward the front of the mouth, and with the lips unrounded: the e in feet. There are others used in American English. There are some combinations of lip and tongue positions that do not correspond to a vowel in English, but do so in other languages. Even finer distinctions in tongue and lip positions have been used for describing vowel sounds with greater precision.

Consonants

Consonant sounds are, like vowel sounds, distinguished by how they are produced. Consonant formation involves stopping or impeding the flow of air from the lungs. This stopping or impeding can occur at various places in the vocal tract and involve various parts of its anatomy: the lips, the tongue, the teeth, the glottis, and the palate. The vocal cords can also be involved during the production of a consonant. The assortment of consonant sounds is quite broad, because so many different combinations of vocal tract actions can be involved. Spoken American English involves only a subset of the many possible consonants, and these are described in what follows.

Consonants that involve the vocal cords during production are called voiced consonants. Examples include the m in mat and r in run. Those produced without using the vocal cords are called voiceless consonants. Examples include the s in sat and the p in pun.

Consonant sounds are also categorized by the location in the vocal tract where the air stream is stopped or impeded. This can happen in any of these locations: at the lips, at the teeth, at the ridge just behind the upper teeth (called the alveolar ridge), at the roof of the mouth (the hard palate), and at the soft palate at the back of the mouth (also called the velum).

In American English, the g sound in go and the k sound in kin are produced when the back of the tongue is pressed against the velum. They are called velar sounds. These two differ in voicing, the g sound is voiced and the k sound is voiceless.

The alveolar ridge is involved in forming the sounds of d in dog, and t in tin. These are alveolar consonants in American English. The d and t differ in voicing, the d sound is voiced and the k sound is voiceless.

The two lips are involved in forming the sounds of b in bit and the p in pit. These are bilabial (two-lipped) consonants. The b and p differ in voicing, the b sound is voiced and the p sound is voiceless.

The lower lip and the upper teeth are involved in producing the sounds of v in vat and f in fat. These consonants are called labiodental (lip-teeth) consonants. The v is a voiced consonant, while the f is unvoiced.

The roof of the mouth is used along with the tongue to produce the consonants represented in American English by the sh in ship and the ch in chip. Neither of these sounds is voiced, both are produced without using the vocal cords. They differ in how they obstruct the air flow from the lungs. In producing the sh sound the air from the lungs is forced to pass through a narrow opening formed by holding the tongue against the roof of the mouth. The turbulence caused by the air through a narrow opening produces the sound. A consonant formed in this way is called a fricative. In producing the ch sound, the air flow from the lungs is briefly blocked completely, then suddenly released. A consonant produced by a complete blocking of the air flow is called a stop. The sh sound is a voiceless palatal fricative, and the ch sound is a voiceless palatal stop.

Now begin to say the word ship. Again, notice how you lift your tongue up to the roof of your mouth. The sh sound is a palatal consonant. If you hold your mouth in position to begin the word ship and try to exhale, air will pass through your mouth, although the flow is somewhat restricted compared to when you breathe normally through your mouth. The sh sound is a fricative.

We have already encountered consonants that are stops. Both the b in bit and the p in pit are stops. Both involve completely stopping the flow of air through the mouth, allowing the pressure to build somewhat, and then suddenly releasing it. In both cases, the stoppage occurs when the lips are pressed together. The difference between them is whether the vocal cords are used in producing the sound. The vocal cords are involved in producing b, so it is a voiced bilabial stop. The vocal cords are not used in producing p, so it is a voiceless bilabial stop.

Stops can be produced in other locations in the mouth as well. A stop can be created with the tip of the tongue pressed against the alveolar ridge, which is at the top front of the mouth, just behind the teeth. The t in tin and the d in din both involve pressing the tongue against the alveolar ridge. The difference between the t and d sounds is the time at which the vocal cords vibrate when the sound is produced.

A stop can also be produced by pressing the tongue against the soft palate at the back of the roof of the mouth, which is also called the velum. The sounds of the initial consonants in the English words gin and kin are velar stops, the g is voiced and the k is voiceless.

Many consonants are produced not by a complete stopping of the air flow from the lungs, but by constricting the flow in some way and forcing it through a narrowed opening. Consonants produced in this way are called fricatives. Fricatives can be formed by forcing air between the upper teeth and lower lip when these are pressed together. These are called labiodental fricatives. The consonants at the start of the words van and fan are examples, the former being a voiced labiodental fricative and the latter an unvoiced labiodental fricative.

Other fricatives are formed by placing the front of the tongue against the alveolar ridge at the top front of the mouth, behind the teeth, and forcing air between them. The consonants at the beginning of the words zip and sip are formed this way, and are called alveolar fricatives, the first being voiced and the second unvoiced.

Fricatives can also be produced by pressing the upper teeth onto the tongue and forcing air between them, as in the initial sound in the word thin. This sound is an unvoiced dental fricative. The voiced dental fricative is the initial sound in the word then.

When the tongue is held against the palate and air forced between them, palatal fricative consonants can be formed. The consonant sound in the middle of the word fashion is an unvoiced palatal fricative, and the consonant sound in the middle of the word vision is a voiced palatal fricative.

A fricative can also be formed by constricting the airway by tightening the vocal cords, which narrows the opening between them, called the glottis, and forcing air between them. Because the vocal cords are tightened, they cannot vibrate, so only an unvoiced glottal fricative is possible. This is the breathy consonant sound at the beginning of the word happy.

Some consonants are produced by vibrating the vocal cords and shaping the vocal tract in such a way as to produce particular resonances. Some of these resonances involve the nasal cavity, and the consonants so formed are called nasal. The sound at the beginning of the word mud is a bilabial nasal, produced by pressing the two lips together, vibrating the vocal cords, and slowly exhaling through the nose. This causes the sound to resonate in the nasal cavity.

A similar sound is that at the beginning of the word net, which is an alveolar nasal, formed by pressing the tongue to the alveolar ridge, vibrating the vocal cords, and slowly exhaling through the nose. A third nasal consonant is produced by pressing the back of the tongue to the back of the palate, the velum, vibrating the vocal cords, and exhaling slowly through the nose. This velar nasal is the consonant sound at the end of the word ring. English has no words beginning with this sound, nor do any other European languages, but many African and Asian languages do.

The mouth itself can also serve as a resonant cavity in the formation of consonants. The cavity of the mouth can be shaped by the tongue to result in different consonants.

Another consonant that uses resonance of the mouth is formed when the tongue is positioned so the left and right edges of the tongue are placed against the upper teeth at both sides of the mouth. Then, with the lips positioned to form a round mouth opening, the vocal cords are vibrated. The the consonant that this produces is the sound at the beginning of the word ring, namely, the r sound. The consonants formed by resonance in the mouth, such as l and r, are called the liquid consonants.

This chart summarizes the classification of some of the consonants used in American English.

| Production of some consonants in American English. | |||||||

| Manner | Voicing | Location | |||||

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Interdental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | ch | k | ||

| Voiced | b | d | g | ||||

| Fricative | Voiceless | f | th(in) | s | sh | h |

|

| Voiced | v | th(en) | z | ||||

| Nasal | Voiced | m | n | ng | |||

| Liquid | Voiced | l | r | ||||